HOLD IT WITHOUT RIPPING IT

Klaus von Gaffron & Paula Leal Olloqui

Neue Galerie Landshut, 2017

Installation

Holz, Stoff, Beton, Klebeband, Neonlicht, Metall, Plastikfolie, Farbe

Installation

Wood, fabric, concrete, duct tape, neon light, metal, plastic foil, colours

Fotos/photographs: Paula Leal Olloqui, Fabian Feichter

Klaus von Gaffron ist in Landshut kein Unbekannter. Bereits vor mehr als 30 Jahren hat er eine

der ersten Ausstellungen in der damaligen Galerie am Maxwehr bestritten und hat seither

mehrmals in der Neuen Galerie Landshut ausgestellt. Gaffron, der sich auch als Kurator und als

erster Vorsitzender des Berufsverbands BBK München und Oberbayern einen Namen gemacht

hat, ist für seine charakteristische Form der experimentellen Fotografie bekannt.

Was seine Fotobilder charakterisiert, ist, dass sie tatsächlich eher wie Tafelbilder, wie in sich gekehrte Tableaus wirken, die eigentlich kein Gegenüber brauchen, die vielmehr in einer in sich versunkenen Verschlossenheit anwesend sind.

Bei Gaffron ist alles Erzählerische eliminiert; wir finden nichts Gegenständliches oder Figuratives, auch wenn wir immer den Eindruck haben, wenn man nur scharf genug schaute, dann würde man das Dargestellte schon noch erkennen.

Tatsächlich sind ja seine Motive Alltagsgegenstände, die er allerdings bis zur Auflösung der Formen verfremdet.

So steht am Anfang also etwas, was man realistisch nennen könnte, sozusagen ein Bild- Ausschnitt von Welt; dies wird aber beim Akt des Fotografierens soweit reduziert, verunklärt und abstrahiert, dass alles Wiedererkennbare abhanden kommt. Bei Gaffron geschieht dies nicht in der digitalen Nachbehandlung auf dem Computer, sondern durch „analoge“ Techniken während des Fotografierens, durch Ausschnitt, extreme Nähe, Bewegung, Unschärfe.

Es ist also weniger die technische und elektronische Manipulation, sondern der horchende Blick des Fotografen im Bildakt selbst, der dann Bilder von einer Welthaltigkeit zeugt, die nichts mehr repräsentieren, und die gerade dadurch eine Präsenz erzeugen, die völlig unvermittelt wirkt - beinahe wie das Erscheinen von etwas, das sich wie ein Fotogramm direkt auf dem empfindlichen Papier abdrückt und das so flüchtig wirkt wie der blitzende Moment, in dem ein kleiner Helligkeitsunterschied auf der Netzhaut im Augenwinkel wahrgenommen wird.

In diesem Moment scheint sich eine dünne äußerste Schicht von den Dingen zu lösen, die nicht mehr das Objekt selbst in sich trägt, sondern bestenfalls eine Erinnerung daran - eine Erinnerung, die dabei ist, zu entschwinden. In den letzten Serien, die in der Ausstellung zu sehen sind, treibt er diese Auflösung beinahe bis zum Äußersten, so dass nur noch vereinzelte Lichtpunkte in monochromen Flächen zurückbleiben, oder gar nur die reine Farb-Oberfläche selbst. Man fühlt sich an konkrete Malerei erinnert, in der die Farbe an sich zum Inhalt wird, doch sind es bei Gaffron die völlig immateriellen Phänomene von Licht- und Farberscheinung, die sich auf den Bildträger legen, so ephemer wie ein Atem-Hauch auf einem Spiegel. Selbst die Bildtitel scheinen in dieser Auflösung befindlich zu sein, bestehen sie doch nur noch aus Wortfragmenten, die wie das Verschwinden einer Sprache anmuten oder an das Entstehen einer solchen.

Und entsprechend sind diese Bilder labile Aggregatszustände des Verschwindens ebenso wie solche des Erscheinens. Sie sind geistig und zugleich ziemlich handfest, denn bei aller Immaterialität des Lichts beziehen sie sich immer auf einen realen Gegenstand, der am Anfang des Bildprozesses steht.

Und deshalb haben wir es auch nie mit rein monochromen Flächen zu tun. Manchmal verströmt sich das Schwarz an den Rändern in ein dunkles Purpur, manchmal gibt es auch nur leichte Temperaturunterschiede, die auf eine Lichtquelle außerhalb des Bildes verweisen. Immer bleibt der Wahrnehmung des Betrachters überlassen, ob er sich auf die Tiefe dieser Bilder einlässt oder ob er sich mit deren Oberfläche zufrieden gibt.

Einer zugegeben sehr delikaten Oberfläche. Auch auf der Ebene funktioniert diese Ausstellung, ja es ist verblüffend, wie sehr die Arbeiten beider Künstler auf ganz unterschiedlichen Ebenen interagieren, welch breite Assoziations- oder besser: Anmutungsspielräume sie eröffnen.

Paula Leal Olloqui, geboren 1984 in Madrid, studierte dort Bildhauerei und ging dann nach München, wo sie zuletzt bei Olaf Metzel ihr Diplom machte - und den Debütantenpreis gewann. Paula Leal Olloquis Arbeiten sind unmittelbar für den besonderen Ort des Gotischen Stadels im Dialog mit den Fotobildern Klaus Gaffrons entstanden.

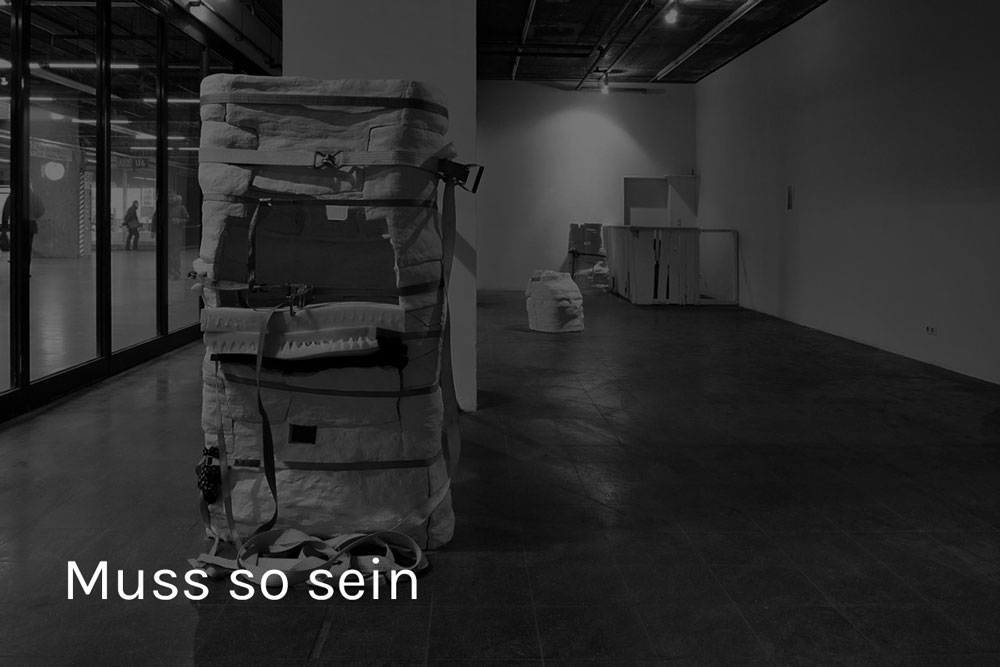

Als wir am vergangenen Montag die Materialien - die Spanplatte, die Latten, die Schaumstoff- und Holz-Reste - aus dem Transporter ausluden, waren gerade Bauarbeiter beim Rauchensteinerhaus beschäftigt. Sie machten uns höflich Platz, damit wir diese Dinge zu ihrem Altwaren-Container bringen konnten und schauten uns etwas überrascht zu, als wir sie jedoch zur Galerie transportierten.

Diese „armen“ Materialien“ waren von der Künstlerin gezielt ausgewählt und vorbereitet, um skulpturale Installationen zu schaffen, welche auf die Arbeiten von Klaus Gaffron und vor allem auf die beiden Räume des Gotischen Stadels Bezug nehmen, mit ihnen interagieren und sie zugleich neu interpretieren, ja in bestimmter Weise auch verändern.

Und wirklich, wenn man ihnen nun wieder begegnet, haben sich diese einzelnen Bestandteile und Materialien in ihren komplexen, labilen Arrangements völlig verändert, sind vom Material zur Skulptur geworden.

Nun könnte man einwenden, dies sei nicht erst seit Duchamps so, dass zu Kunst wird, was der Künstler macht bzw. was auf einem Sockel respektive in einem Ausstellungsraum präsentiert wird.

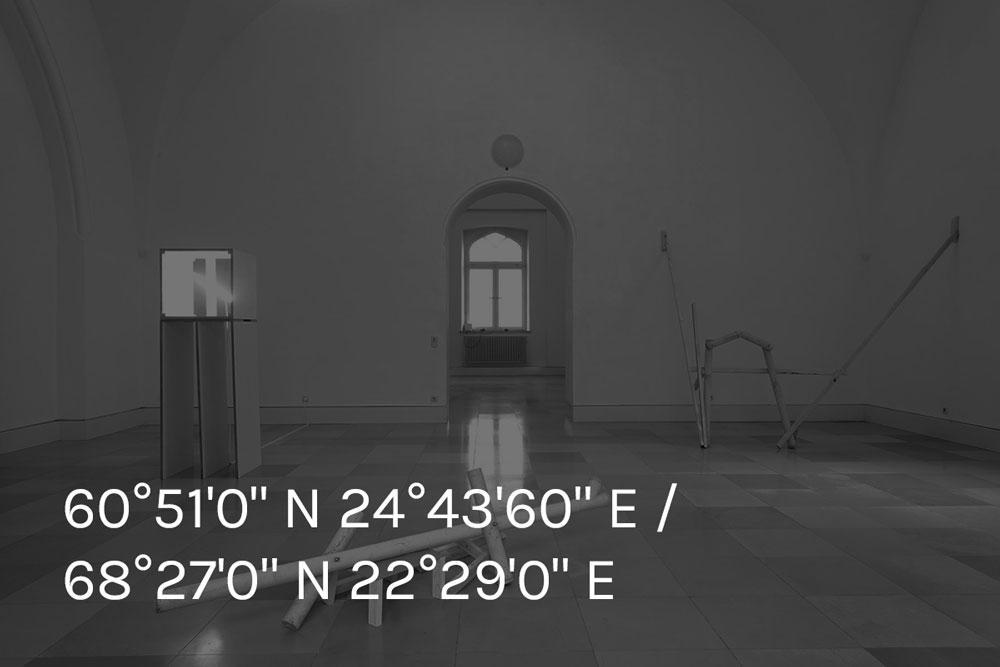

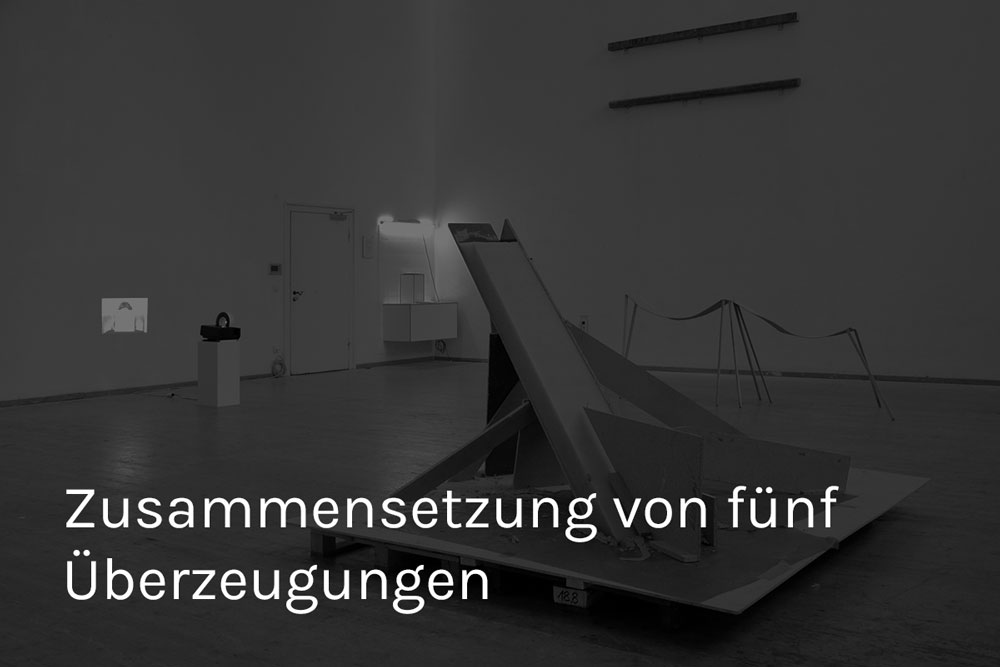

Dann geht man allerdings in den zweiten Stock, in diesen offenen und weiten Raum, und ist vom ersten Eindruck gefangen genommen. Dieser wirkt nicht wie üblich als ein Ausstellungsraum, sondern wie eine Inszenierung, in der alles aufeinander Bezug nimmt. Dabei sind die einzelnen Objekte aus ganz wenigen, einfachen Bestandteilen gefertigt. Zwei Balken, spitz aufeinander zulaufend, darauf zwei Metallstangen, welche wie ein Rahmen eine Holzplatte halten, die sich wie ein Bogen darüber spannt. In der Mitte des Raumes, aus der Zentralachse verschoben, ein einfacher Lattenrahmen, teilweise verschraubt, teilweise mit Tape verklebt, welcher ein paar Schaumstoffteile aufnimmt, auf denen ein textile Gebilde zu liegen kommt, welches durch Gips in eine permanent geschwungene Form gebracht wurde.

Und am Anfang des Raumes, zunächst nur von der Rückseite her zu sehen und damit auch gleich ihre Kulissenhaftigkeit preisgebend, eine konkave Form, die von einer mit Abdeckfolie bespannten Spanplatte gebildet wird. Man könnte auch sagen: Baldachin, Liege, Hohlspiegel und würde damit klassische oder klassizistische Standardformen der Repräsentation von Würde, Hoheit, ja Heiligkeit aufzählen. Die purpurne Fläche des Fotobildes von Klaus Gaffron tut ein Übriges, und es fällt schwer, sich von dem Gedanken zu trennen, hier stünde man vor einem leibhaftigen Zitat eines Bildes von Jacques-Louis David oder Ingres.

Doch bei aller Freiheit der Assoziation wäre man hier auf einem Holzweg. Die Bezüglichkeiten sind deutlich immanenter und holen uns zurück in den Raum, für den diese Arbeiten geschaffen wurden: Das gewählte Material greift immer wieder auf das Material des Gotischen Stadels zurück, zitiert es jedoch jeweils mit leichten, präzise gesetzten Verschiebungen.

Das konkave Objekt etwa besteht aus dem gleichen Material wie die Seitenwände; in seiner Gebogenheit eignet es sich allerdings nicht für die Aufnahme von Bildern.

Die Balken des gotischen Baus finden wir wieder in der Bogenskulptur; und wenn wir in Gedanken das Objekt um 90° drehen, meint man fast, ein grobes Modell des Stadels selbst vor sich liegen zu haben.

Im unteren Stockwerk wiederum scheint das beleuchtete kastenartige Objekt eine humorvolle Bezugnahme zur Küchenzeile zu bilden...

und schon sind wir wieder in den bildhaften, inhaltlichen Assoziationsfeldern und koppeln unsere Wahrnehmung zu schnell mit unseren eigenen Bild- und Erinnerungsspeicher. Schauen wir nochmals etwas genauer hin, dann sehen wir und spüren wir, wie die wenigen, aber gezielt platzierten Konstruktionen den Raum in Bewegung bringen. Das Bogenobjekt öffnet sich präzise aus der hinteren Ecke in den Raum, dieser Bogen mündet in eine wellenartige Verwerfung in dem liegenden Objekt und wird aufgefangen von der konkaven Form am anderen Ende des Raumes. Diese konkave Form korrespondiert mit der konvexen Biegung des Baldachins, bekommt aber durch die Umhüllung mit der Abdeckfolie eine ganz andere, materielle Anmutung von Glanz und Weichheit.

Was die alle Arbeiten verbindet, ist die Labilität ihrer Konstruktion. Die konkave Form etwa ist nur mit einem winzigen Holzkeil zwischen die Fugen des Dielenbodens gespannt. So manches scheint gefährdet wegzurollen, sich zusammenzufalten, umzustürzen. Und doch hält die innere Spannung.

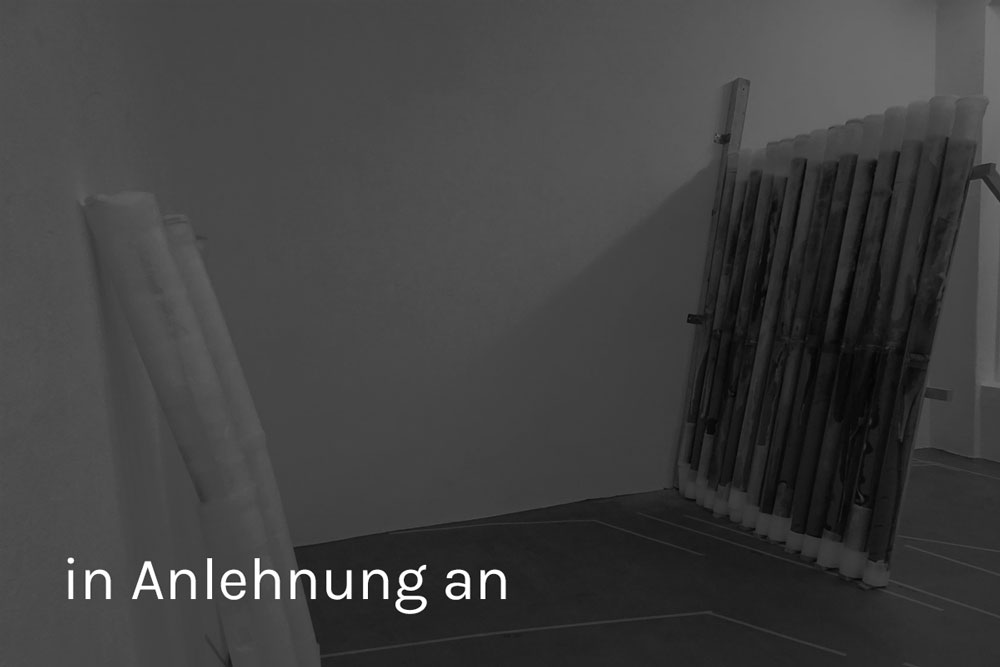

Hin und wieder suggerieren manche Skulpturen eine - uns sich nicht erschließende - Funktionalität, manchmal nehmen auch Teile von Skulpturen beinahe funktionale Bedeutung an: Die verschieden verschatteten Flächen der geometrischen Kasten-Form etwa treten nur durch den Einsatz einer Leuchtstoffröhre zu Tage, die zugleich impliziter Bestandteil des Objektes ist. Ähnliches gilt für die Wandhalterungen oder Gestelle der Betonröhren, die zwar diese Röhren wie für einen ganz bestimmten Zweck in einem besonderen Winkel halten sollen, der sich aber wiederum dem Betrachter nicht erschließt.

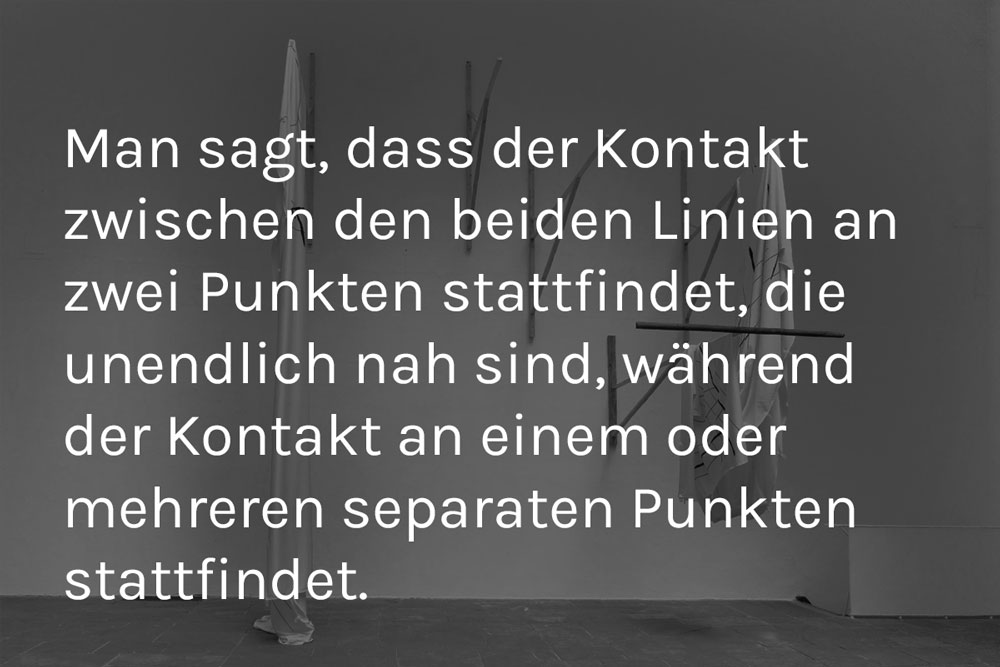

Wir sollten unseren Blick deshalb nochmals etwas schärfer auf die einzelnen Objekte richten. Und da geben uns die Titel der Arbeiten verblüffend klare Hinweise. So lautet derjenige für das letztgenannte Objekt: „Vier verlängerte Kreise in Bewegung, die sich zusammenschließen in wohldefiniertem Winkel“

Wir müssen also nicht außerhalb der Skulptur suchen: Genau das ist es, was hier vor sich geht, und was unsere Augen und unsere Vorstellungskraft nachvollziehen können.

Bei aller scheinbar beiläufigen, zunächst wie zufällig anmutenden Erscheinung der Skulpturen: Material, Form, Konstruktion und Konstellation sind die stets präzise definierten Determinanten dieser installativen Arbeiten. So auch bei der zweiteiligen Skulptur an Wand und Boden: „Dreidimensionale geometrische Zusammensetzungen, hart und vertikal, einer dreidimensionalen geometrischen Zusammensetzung weich und horizontal gegenüber gestellt, die sich ausdehnen und im Zwischenraum zwischen beiden Formen sich treffen.“

In ihrer so klar und doch so offen definierten Beschaffenheit und ihrer labilen Konstruiertheit entwickeln diese Skulpturen eine Dynamik, die sich zunächst in ihrem Inneren anbahnt, die dann aus ihnen heraus strebt, so dass sie zueinander - und zum Raum - in eine tänzelnde Bewegung geraten und dadurch auch unsere Wahrnehmung, wenn wir diese Bewegung mitmachen, in Schwingung versetzen.

Für alle Arbeiten in dieser Ausstellung jedenfalls gilt es, unserer unverstellten Wahrnehmung zu vertrauen, zum Sichtbaren zurückzukehren und uns dem sinnlich Erfahrbaren zu öffnen. Wenn dann unsere Assoziationen ins Taumeln geraten und mit uns durchgehen - bitteschön.

(Text: Franz Schneider, 2017)

Was seine Fotobilder charakterisiert, ist, dass sie tatsächlich eher wie Tafelbilder, wie in sich gekehrte Tableaus wirken, die eigentlich kein Gegenüber brauchen, die vielmehr in einer in sich versunkenen Verschlossenheit anwesend sind.

Bei Gaffron ist alles Erzählerische eliminiert; wir finden nichts Gegenständliches oder Figuratives, auch wenn wir immer den Eindruck haben, wenn man nur scharf genug schaute, dann würde man das Dargestellte schon noch erkennen.

Tatsächlich sind ja seine Motive Alltagsgegenstände, die er allerdings bis zur Auflösung der Formen verfremdet.

So steht am Anfang also etwas, was man realistisch nennen könnte, sozusagen ein Bild- Ausschnitt von Welt; dies wird aber beim Akt des Fotografierens soweit reduziert, verunklärt und abstrahiert, dass alles Wiedererkennbare abhanden kommt. Bei Gaffron geschieht dies nicht in der digitalen Nachbehandlung auf dem Computer, sondern durch „analoge“ Techniken während des Fotografierens, durch Ausschnitt, extreme Nähe, Bewegung, Unschärfe.

Es ist also weniger die technische und elektronische Manipulation, sondern der horchende Blick des Fotografen im Bildakt selbst, der dann Bilder von einer Welthaltigkeit zeugt, die nichts mehr repräsentieren, und die gerade dadurch eine Präsenz erzeugen, die völlig unvermittelt wirkt - beinahe wie das Erscheinen von etwas, das sich wie ein Fotogramm direkt auf dem empfindlichen Papier abdrückt und das so flüchtig wirkt wie der blitzende Moment, in dem ein kleiner Helligkeitsunterschied auf der Netzhaut im Augenwinkel wahrgenommen wird.

In diesem Moment scheint sich eine dünne äußerste Schicht von den Dingen zu lösen, die nicht mehr das Objekt selbst in sich trägt, sondern bestenfalls eine Erinnerung daran - eine Erinnerung, die dabei ist, zu entschwinden. In den letzten Serien, die in der Ausstellung zu sehen sind, treibt er diese Auflösung beinahe bis zum Äußersten, so dass nur noch vereinzelte Lichtpunkte in monochromen Flächen zurückbleiben, oder gar nur die reine Farb-Oberfläche selbst. Man fühlt sich an konkrete Malerei erinnert, in der die Farbe an sich zum Inhalt wird, doch sind es bei Gaffron die völlig immateriellen Phänomene von Licht- und Farberscheinung, die sich auf den Bildträger legen, so ephemer wie ein Atem-Hauch auf einem Spiegel. Selbst die Bildtitel scheinen in dieser Auflösung befindlich zu sein, bestehen sie doch nur noch aus Wortfragmenten, die wie das Verschwinden einer Sprache anmuten oder an das Entstehen einer solchen.

Und entsprechend sind diese Bilder labile Aggregatszustände des Verschwindens ebenso wie solche des Erscheinens. Sie sind geistig und zugleich ziemlich handfest, denn bei aller Immaterialität des Lichts beziehen sie sich immer auf einen realen Gegenstand, der am Anfang des Bildprozesses steht.

Und deshalb haben wir es auch nie mit rein monochromen Flächen zu tun. Manchmal verströmt sich das Schwarz an den Rändern in ein dunkles Purpur, manchmal gibt es auch nur leichte Temperaturunterschiede, die auf eine Lichtquelle außerhalb des Bildes verweisen. Immer bleibt der Wahrnehmung des Betrachters überlassen, ob er sich auf die Tiefe dieser Bilder einlässt oder ob er sich mit deren Oberfläche zufrieden gibt.

Einer zugegeben sehr delikaten Oberfläche. Auch auf der Ebene funktioniert diese Ausstellung, ja es ist verblüffend, wie sehr die Arbeiten beider Künstler auf ganz unterschiedlichen Ebenen interagieren, welch breite Assoziations- oder besser: Anmutungsspielräume sie eröffnen.

Paula Leal Olloqui, geboren 1984 in Madrid, studierte dort Bildhauerei und ging dann nach München, wo sie zuletzt bei Olaf Metzel ihr Diplom machte - und den Debütantenpreis gewann. Paula Leal Olloquis Arbeiten sind unmittelbar für den besonderen Ort des Gotischen Stadels im Dialog mit den Fotobildern Klaus Gaffrons entstanden.

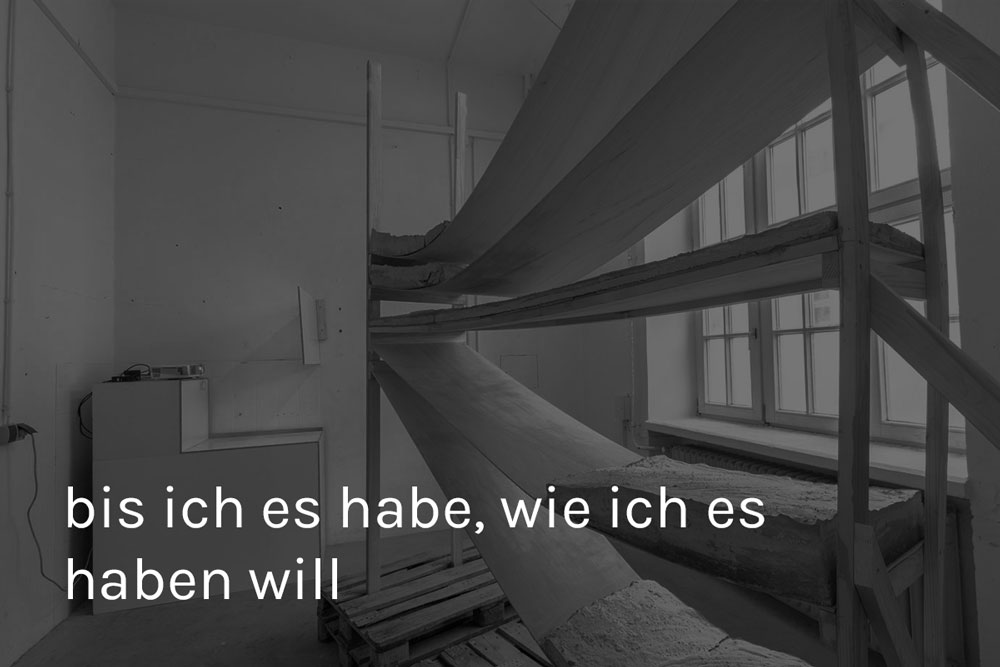

Als wir am vergangenen Montag die Materialien - die Spanplatte, die Latten, die Schaumstoff- und Holz-Reste - aus dem Transporter ausluden, waren gerade Bauarbeiter beim Rauchensteinerhaus beschäftigt. Sie machten uns höflich Platz, damit wir diese Dinge zu ihrem Altwaren-Container bringen konnten und schauten uns etwas überrascht zu, als wir sie jedoch zur Galerie transportierten.

Diese „armen“ Materialien“ waren von der Künstlerin gezielt ausgewählt und vorbereitet, um skulpturale Installationen zu schaffen, welche auf die Arbeiten von Klaus Gaffron und vor allem auf die beiden Räume des Gotischen Stadels Bezug nehmen, mit ihnen interagieren und sie zugleich neu interpretieren, ja in bestimmter Weise auch verändern.

Und wirklich, wenn man ihnen nun wieder begegnet, haben sich diese einzelnen Bestandteile und Materialien in ihren komplexen, labilen Arrangements völlig verändert, sind vom Material zur Skulptur geworden.

Nun könnte man einwenden, dies sei nicht erst seit Duchamps so, dass zu Kunst wird, was der Künstler macht bzw. was auf einem Sockel respektive in einem Ausstellungsraum präsentiert wird.

Dann geht man allerdings in den zweiten Stock, in diesen offenen und weiten Raum, und ist vom ersten Eindruck gefangen genommen. Dieser wirkt nicht wie üblich als ein Ausstellungsraum, sondern wie eine Inszenierung, in der alles aufeinander Bezug nimmt. Dabei sind die einzelnen Objekte aus ganz wenigen, einfachen Bestandteilen gefertigt. Zwei Balken, spitz aufeinander zulaufend, darauf zwei Metallstangen, welche wie ein Rahmen eine Holzplatte halten, die sich wie ein Bogen darüber spannt. In der Mitte des Raumes, aus der Zentralachse verschoben, ein einfacher Lattenrahmen, teilweise verschraubt, teilweise mit Tape verklebt, welcher ein paar Schaumstoffteile aufnimmt, auf denen ein textile Gebilde zu liegen kommt, welches durch Gips in eine permanent geschwungene Form gebracht wurde.

Und am Anfang des Raumes, zunächst nur von der Rückseite her zu sehen und damit auch gleich ihre Kulissenhaftigkeit preisgebend, eine konkave Form, die von einer mit Abdeckfolie bespannten Spanplatte gebildet wird. Man könnte auch sagen: Baldachin, Liege, Hohlspiegel und würde damit klassische oder klassizistische Standardformen der Repräsentation von Würde, Hoheit, ja Heiligkeit aufzählen. Die purpurne Fläche des Fotobildes von Klaus Gaffron tut ein Übriges, und es fällt schwer, sich von dem Gedanken zu trennen, hier stünde man vor einem leibhaftigen Zitat eines Bildes von Jacques-Louis David oder Ingres.

Doch bei aller Freiheit der Assoziation wäre man hier auf einem Holzweg. Die Bezüglichkeiten sind deutlich immanenter und holen uns zurück in den Raum, für den diese Arbeiten geschaffen wurden: Das gewählte Material greift immer wieder auf das Material des Gotischen Stadels zurück, zitiert es jedoch jeweils mit leichten, präzise gesetzten Verschiebungen.

Das konkave Objekt etwa besteht aus dem gleichen Material wie die Seitenwände; in seiner Gebogenheit eignet es sich allerdings nicht für die Aufnahme von Bildern.

Die Balken des gotischen Baus finden wir wieder in der Bogenskulptur; und wenn wir in Gedanken das Objekt um 90° drehen, meint man fast, ein grobes Modell des Stadels selbst vor sich liegen zu haben.

Im unteren Stockwerk wiederum scheint das beleuchtete kastenartige Objekt eine humorvolle Bezugnahme zur Küchenzeile zu bilden...

und schon sind wir wieder in den bildhaften, inhaltlichen Assoziationsfeldern und koppeln unsere Wahrnehmung zu schnell mit unseren eigenen Bild- und Erinnerungsspeicher. Schauen wir nochmals etwas genauer hin, dann sehen wir und spüren wir, wie die wenigen, aber gezielt platzierten Konstruktionen den Raum in Bewegung bringen. Das Bogenobjekt öffnet sich präzise aus der hinteren Ecke in den Raum, dieser Bogen mündet in eine wellenartige Verwerfung in dem liegenden Objekt und wird aufgefangen von der konkaven Form am anderen Ende des Raumes. Diese konkave Form korrespondiert mit der konvexen Biegung des Baldachins, bekommt aber durch die Umhüllung mit der Abdeckfolie eine ganz andere, materielle Anmutung von Glanz und Weichheit.

Was die alle Arbeiten verbindet, ist die Labilität ihrer Konstruktion. Die konkave Form etwa ist nur mit einem winzigen Holzkeil zwischen die Fugen des Dielenbodens gespannt. So manches scheint gefährdet wegzurollen, sich zusammenzufalten, umzustürzen. Und doch hält die innere Spannung.

Hin und wieder suggerieren manche Skulpturen eine - uns sich nicht erschließende - Funktionalität, manchmal nehmen auch Teile von Skulpturen beinahe funktionale Bedeutung an: Die verschieden verschatteten Flächen der geometrischen Kasten-Form etwa treten nur durch den Einsatz einer Leuchtstoffröhre zu Tage, die zugleich impliziter Bestandteil des Objektes ist. Ähnliches gilt für die Wandhalterungen oder Gestelle der Betonröhren, die zwar diese Röhren wie für einen ganz bestimmten Zweck in einem besonderen Winkel halten sollen, der sich aber wiederum dem Betrachter nicht erschließt.

Wir sollten unseren Blick deshalb nochmals etwas schärfer auf die einzelnen Objekte richten. Und da geben uns die Titel der Arbeiten verblüffend klare Hinweise. So lautet derjenige für das letztgenannte Objekt: „Vier verlängerte Kreise in Bewegung, die sich zusammenschließen in wohldefiniertem Winkel“

Wir müssen also nicht außerhalb der Skulptur suchen: Genau das ist es, was hier vor sich geht, und was unsere Augen und unsere Vorstellungskraft nachvollziehen können.

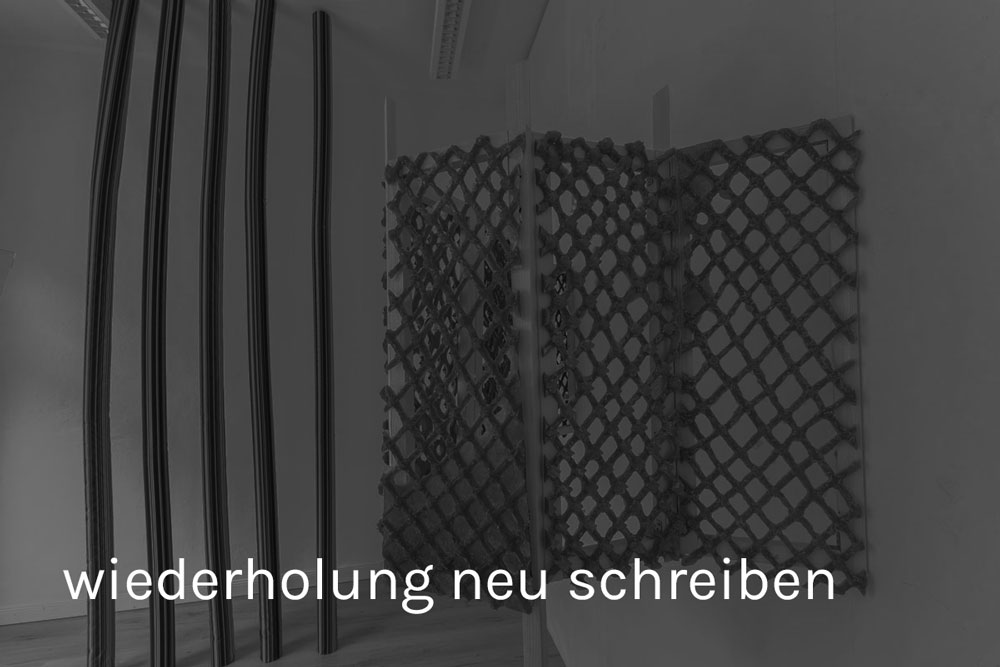

Bei aller scheinbar beiläufigen, zunächst wie zufällig anmutenden Erscheinung der Skulpturen: Material, Form, Konstruktion und Konstellation sind die stets präzise definierten Determinanten dieser installativen Arbeiten. So auch bei der zweiteiligen Skulptur an Wand und Boden: „Dreidimensionale geometrische Zusammensetzungen, hart und vertikal, einer dreidimensionalen geometrischen Zusammensetzung weich und horizontal gegenüber gestellt, die sich ausdehnen und im Zwischenraum zwischen beiden Formen sich treffen.“

In ihrer so klar und doch so offen definierten Beschaffenheit und ihrer labilen Konstruiertheit entwickeln diese Skulpturen eine Dynamik, die sich zunächst in ihrem Inneren anbahnt, die dann aus ihnen heraus strebt, so dass sie zueinander - und zum Raum - in eine tänzelnde Bewegung geraten und dadurch auch unsere Wahrnehmung, wenn wir diese Bewegung mitmachen, in Schwingung versetzen.

Für alle Arbeiten in dieser Ausstellung jedenfalls gilt es, unserer unverstellten Wahrnehmung zu vertrauen, zum Sichtbaren zurückzukehren und uns dem sinnlich Erfahrbaren zu öffnen. Wenn dann unsere Assoziationen ins Taumeln geraten und mit uns durchgehen - bitteschön.

(Text: Franz Schneider, 2017)

Klaus von Gaffron is no stranger to Landshut. More than 30 years ago he realized one of the first exhibitions in the Galerie am Maxwehr and since then he exhibited several times in the Neue Galerie Landshut. Gaffron, who also made a name for himself as a curator and as the first chairman of the professional artists association BBK Munich and Upper Bavaria, is known for his characteristic form of experimental photography.

What characterizes his photographic images is that they actually look more like panel paintings, like introspective tableaus that actually don't need a counterpart, that are rather present in a secluded retreat.

With Gaffron, every narrative is eliminated; we don't find anything representational or figurative, yet we always have the impression that if we would look sharply enough, we would recognize what is depicted.

In fact, his motifs are everyday objects, which he alienates until the forms are dissolved.

So at the beginning there is something that could be called realistic, a picture-section of the world, so to speak; however, in the act of photographing this is reduced, obscured and abstracted to such an extent that everything recognizable is lost. In Gaffrons works, this is not done in the digital post-processing on the computer, but through "analog" techniques during photography, through cropping, extreme closeness, movement, and blurring.

It is less the technical and electronic manipulation, but the listening gaze of the photographer in the act of taking an image itself, which leads to images that no longer represent anything, and which create a presence that appears completely immediate - almost like the appearance of something that is imprinted directly on the sensitive paper like a photogram and that seems as fleeting as the flashing moment in which a small difference in brightness is perceived on the retina in the corner of the eye.

At this moment, a thin, outermost layer seems to peel off, which no longer contains the object itself, but a memory of it - a memory that is about to disappear. In the last series that can be seen in the exhibition, he takes this dissolution almost to the extreme, so that only isolated points of light remain in monochrome surfaces, or even only the pure color surface itself. One feels reminiscent of Concrete Painting , in which the color itself becomes the content, but with Gaffron it is the completely immaterial phenomena of light and color that lie on the picture carrier, as ephemeral as a breath on a mirror. Even the picture titles seem to be in this state of resolution, since they only consist of word fragments that seem like the disappearance of a language or the emergence of one.

And in accordance these images are unstable aggregate states of disappearance as well as of appearance. They are spiritual and at the same time quite tangible, because despite all the immateriality of light, they always refer to a real object that stood at the beginning of the image process.

That's why we never see purely monochrome surfaces. Sometimes the black fades into a dark purple at the edges, sometimes there are only slight differences in temperature that point to a light source outside the picture. It is always left to the perception of the viewer whether he gets involved in the depth of these images or whether he is satisfied with their surface.

Admittedly a very delicate surface. This exhibition also works on this level, yes, it is amazing how much the works of both artists interact on very different levels, what broad associations, or better: freedom of impression, they open up.

Paula Leal Olloqui, born in Madrid in 1984, studied sculpture in her native city and then went to Munich, where she graduated in the class of Olaf Metzel - and won the debutant award. Paula Leal Olloqui's works were created directly for the special location of the Gothic barn in dialogue with the photo images of Klaus von Gaffron.

When we unloaded the materials - the chipboard, the slats, the foam and wood scraps - from the transporter last Monday, construction workers were working at the Rauchsteinerhaus. They politely made room for us so that we could take these things to their junk container and looked with a bit of surprise when we transported them to the gallery.

These "poor" materials were specifically selected and prepared by the artist in order to create sculptural installations that refer to the works of Klaus von Gaffron and above all to the two rooms of the Gothic Stadel, to interact with them and at the same time reinterpret them, and yes, also change them in a certain way.

And really, when you meet them again, these individual components and materials have completely changed in their complex, unstable arrangements, have turned from material to sculpture.

One could argue that it was not just since Duchamps that what the artist does or what is presented on a pedestal or in an exhibition space becomes art.

But then you go to the second floor, in this open and wide room, and are captured by the first impression. This does not look like an usual exhibition space, but like a staging in which everything relates to one another. The individual objects are made from very few, simple components. Two beams, tapering to a point, on top of which are two metal rods, holding a wooden panel like a frame, which spans over it like an arch. In the middle of the room, shifted from the central axis, a simple slatted frame, partly screwed, partly glued with tape, holding a few pieces of foam on which a textile structure, that was brought into a permanently curved shape by plaster, comes to lie.

And at the beginning of the room, initially only visible from the back and thus revealing its backdrop, a concave shape that is formed by a chipboard covered with a tarpaulin. One could also say: canopy, lounger, concave mirror and would thus enumerate classic or classicist standard forms of representation of dignity, sovereignty, even holiness. The purple surface of the photo by Klaus von Gaffron does the rest, and it’s difficult to part with the thought that one is standing in front of a real quotation of a picture by Jacques-Louis David or Ingres.

But with all the freedom of association, one would be on the wrong track here. The references are much more immanent and bring us back to the space for which these works were created: The material chosen always draws on the material of the Gothic barn, but cites it with slight, precisely placed shifts.

The concave object, for example, is made of the same material as the side walls; however, its curvature is not suitable for taking pictures.

The beams of the Gothic building can be found in the arched sculpture; and when we turn the object by 90 ° in our mind, we almost thinks that we have a rough model of the barn itself in front of us.

On the lower floor, on the other hand, the illuminated box-like object seems to form a humorous reference to the kitchen unit ...

and then we are back in the pictorial, content-related fields of association and too quickly we couple our perception with our own image and memory storage. If we take a closer look again, we see and feel how the few, but carefully placed constructions set the room in motion. The arched object opens precisely from the rear corner into the room, this arch ends in a wave-like warp in the lying room and is caught by the concave shape at the other end of the room. This concave shape corresponds to the convex curve of the canopy, but is given a completely different, material impression of shine and softness due to the covering with the tarpaulin.

What connects all of the works is the instability of their construction. The concave shape, for example, is only stretched between the joints of the plank floor with a tiny wooden wedge. Some things seem to be in danger of either rolling away, folding themselves up, or overturning. And yet the inner tension holds.

Every now and then, some sculptures suggest a functionality that is not accessible to us, sometimes parts of sculptures take on almost functional significance: the variously shaded surfaces of the geometric box shape, for example, only come to light through the use of a fluorescent tube, which is also an implicit component of the object. The same applies to the wall brackets or frames of the concrete pipes, which are supposed to hold these pipes at a special angle, as if for a very specific purpose, which is not accessible to the viewer.

We should therefore focus our gaze a little more sharply on the individual objects. And the titles of the works give us amazingly clear indications. The one for the last-mentioned object reads: "Four elongated circles in motion that join together at a well-defined angle"

So we don't have to look outside the sculpture: that is exactly what is going on here and what our eyes and imagination can understand.

In spite of all the seemingly incidental, seemingly random appearance of the sculptures: material, form, construction and constellation are the always precisely defined determinants of these installation works. This is also the case with the two-part sculpture on the wall and floor: "Three-dimensional geometrical compositions, hard and vertical, juxtaposed with a three-dimensional geometrical composition soft and horizontally, which expand and meet in the space between the two forms."

In their clear and yet so openly defined nature and their unstable construction, these sculptures develop a dynamic that initially emerges in their inside, which then strives out of them, so that they come into a prancing movement towards each other - and towards the space - and thereby they also set our perception in vibration when we participate in this movement.

For all of the works in this exhibition, it is important to trust our undisguised perception, to return to the visible and to open up to what can be sensually experienced. If our associations start to tumble and run off with us - here you go.

(Text: Franz Schneider, 2017)

What characterizes his photographic images is that they actually look more like panel paintings, like introspective tableaus that actually don't need a counterpart, that are rather present in a secluded retreat.

With Gaffron, every narrative is eliminated; we don't find anything representational or figurative, yet we always have the impression that if we would look sharply enough, we would recognize what is depicted.

In fact, his motifs are everyday objects, which he alienates until the forms are dissolved.

So at the beginning there is something that could be called realistic, a picture-section of the world, so to speak; however, in the act of photographing this is reduced, obscured and abstracted to such an extent that everything recognizable is lost. In Gaffrons works, this is not done in the digital post-processing on the computer, but through "analog" techniques during photography, through cropping, extreme closeness, movement, and blurring.

It is less the technical and electronic manipulation, but the listening gaze of the photographer in the act of taking an image itself, which leads to images that no longer represent anything, and which create a presence that appears completely immediate - almost like the appearance of something that is imprinted directly on the sensitive paper like a photogram and that seems as fleeting as the flashing moment in which a small difference in brightness is perceived on the retina in the corner of the eye.

At this moment, a thin, outermost layer seems to peel off, which no longer contains the object itself, but a memory of it - a memory that is about to disappear. In the last series that can be seen in the exhibition, he takes this dissolution almost to the extreme, so that only isolated points of light remain in monochrome surfaces, or even only the pure color surface itself. One feels reminiscent of Concrete Painting , in which the color itself becomes the content, but with Gaffron it is the completely immaterial phenomena of light and color that lie on the picture carrier, as ephemeral as a breath on a mirror. Even the picture titles seem to be in this state of resolution, since they only consist of word fragments that seem like the disappearance of a language or the emergence of one.

And in accordance these images are unstable aggregate states of disappearance as well as of appearance. They are spiritual and at the same time quite tangible, because despite all the immateriality of light, they always refer to a real object that stood at the beginning of the image process.

That's why we never see purely monochrome surfaces. Sometimes the black fades into a dark purple at the edges, sometimes there are only slight differences in temperature that point to a light source outside the picture. It is always left to the perception of the viewer whether he gets involved in the depth of these images or whether he is satisfied with their surface.

Admittedly a very delicate surface. This exhibition also works on this level, yes, it is amazing how much the works of both artists interact on very different levels, what broad associations, or better: freedom of impression, they open up.

Paula Leal Olloqui, born in Madrid in 1984, studied sculpture in her native city and then went to Munich, where she graduated in the class of Olaf Metzel - and won the debutant award. Paula Leal Olloqui's works were created directly for the special location of the Gothic barn in dialogue with the photo images of Klaus von Gaffron.

When we unloaded the materials - the chipboard, the slats, the foam and wood scraps - from the transporter last Monday, construction workers were working at the Rauchsteinerhaus. They politely made room for us so that we could take these things to their junk container and looked with a bit of surprise when we transported them to the gallery.

These "poor" materials were specifically selected and prepared by the artist in order to create sculptural installations that refer to the works of Klaus von Gaffron and above all to the two rooms of the Gothic Stadel, to interact with them and at the same time reinterpret them, and yes, also change them in a certain way.

And really, when you meet them again, these individual components and materials have completely changed in their complex, unstable arrangements, have turned from material to sculpture.

One could argue that it was not just since Duchamps that what the artist does or what is presented on a pedestal or in an exhibition space becomes art.

But then you go to the second floor, in this open and wide room, and are captured by the first impression. This does not look like an usual exhibition space, but like a staging in which everything relates to one another. The individual objects are made from very few, simple components. Two beams, tapering to a point, on top of which are two metal rods, holding a wooden panel like a frame, which spans over it like an arch. In the middle of the room, shifted from the central axis, a simple slatted frame, partly screwed, partly glued with tape, holding a few pieces of foam on which a textile structure, that was brought into a permanently curved shape by plaster, comes to lie.

And at the beginning of the room, initially only visible from the back and thus revealing its backdrop, a concave shape that is formed by a chipboard covered with a tarpaulin. One could also say: canopy, lounger, concave mirror and would thus enumerate classic or classicist standard forms of representation of dignity, sovereignty, even holiness. The purple surface of the photo by Klaus von Gaffron does the rest, and it’s difficult to part with the thought that one is standing in front of a real quotation of a picture by Jacques-Louis David or Ingres.

But with all the freedom of association, one would be on the wrong track here. The references are much more immanent and bring us back to the space for which these works were created: The material chosen always draws on the material of the Gothic barn, but cites it with slight, precisely placed shifts.

The concave object, for example, is made of the same material as the side walls; however, its curvature is not suitable for taking pictures.

The beams of the Gothic building can be found in the arched sculpture; and when we turn the object by 90 ° in our mind, we almost thinks that we have a rough model of the barn itself in front of us.

On the lower floor, on the other hand, the illuminated box-like object seems to form a humorous reference to the kitchen unit ...

and then we are back in the pictorial, content-related fields of association and too quickly we couple our perception with our own image and memory storage. If we take a closer look again, we see and feel how the few, but carefully placed constructions set the room in motion. The arched object opens precisely from the rear corner into the room, this arch ends in a wave-like warp in the lying room and is caught by the concave shape at the other end of the room. This concave shape corresponds to the convex curve of the canopy, but is given a completely different, material impression of shine and softness due to the covering with the tarpaulin.

What connects all of the works is the instability of their construction. The concave shape, for example, is only stretched between the joints of the plank floor with a tiny wooden wedge. Some things seem to be in danger of either rolling away, folding themselves up, or overturning. And yet the inner tension holds.

Every now and then, some sculptures suggest a functionality that is not accessible to us, sometimes parts of sculptures take on almost functional significance: the variously shaded surfaces of the geometric box shape, for example, only come to light through the use of a fluorescent tube, which is also an implicit component of the object. The same applies to the wall brackets or frames of the concrete pipes, which are supposed to hold these pipes at a special angle, as if for a very specific purpose, which is not accessible to the viewer.

We should therefore focus our gaze a little more sharply on the individual objects. And the titles of the works give us amazingly clear indications. The one for the last-mentioned object reads: "Four elongated circles in motion that join together at a well-defined angle"

So we don't have to look outside the sculpture: that is exactly what is going on here and what our eyes and imagination can understand.

In spite of all the seemingly incidental, seemingly random appearance of the sculptures: material, form, construction and constellation are the always precisely defined determinants of these installation works. This is also the case with the two-part sculpture on the wall and floor: "Three-dimensional geometrical compositions, hard and vertical, juxtaposed with a three-dimensional geometrical composition soft and horizontally, which expand and meet in the space between the two forms."

In their clear and yet so openly defined nature and their unstable construction, these sculptures develop a dynamic that initially emerges in their inside, which then strives out of them, so that they come into a prancing movement towards each other - and towards the space - and thereby they also set our perception in vibration when we participate in this movement.

For all of the works in this exhibition, it is important to trust our undisguised perception, to return to the visible and to open up to what can be sensually experienced. If our associations start to tumble and run off with us - here you go.

(Text: Franz Schneider, 2017)